1 Introduction to Group Dynamics

Psychologists study groups because nearly all aspects of human life—working, learning, worshiping, socializing, playing, and even sleeping—typically happen in group settings. True isolation is rare. Most people spend their lives amid various social groups, which significantly influence their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. While many psychologists concentrate on individuals, social psychologists broaden the lens to examine the dynamics of groups, organizations, communities, and entire cultures.

To understand what it means to be a group member begin by asking: Why are groups so psychologically important? Human beings are inherently social, spending more time in groups than alone. What drives this tendency, and what does it reveal about human psychology? Major research findings on group behavior stem from key questions such as: Do people exert the same effort in groups as they do alone? Are groups more cautious or more extreme in their decisions? Do groups make better choices than individuals CITE? Often, the answers challenge common assumptions and conventional wisdom.

The Psychological Importance of Groups

Many people take pride in being independent and self-reliant. Thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson famously encouraged people to be true to themselves and follow their own paths (CITE). Yet, even with the ability to live alone, most people choose to connect with others. Why? Because being part of a group fulfills important psychological and social needs.

The Need to Belong

Humans have a strong and natural desire to belong. Across cultures and time periods, people consistently prefer being included rather than left out, and accepted rather than rejected. Psychologists Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary described this as a deep-rooted need to form and maintain lasting, positive relationships (CITE).

We often meet this need by joining groups. For instance, nearly 9 out of 10 Americans live with other people—family, partners, or roommates. Many regularly take part in group activities like attending events, eating meals together, or going out with friends (CITE).

When this need isn’t met, people can feel the impact deeply. College students, for example, may experience homesickness and loneliness when they’re not part of a supportive group. On the other hand, being included in a close-knit social group tends to increase happiness and life satisfaction (CITE). In contrast, being rejected or left out can lead to negative feelings like sadness, helplessness, or depression (CITE).

Studies on ostracism—being deliberately excluded—show that it’s not just emotionally painful but also physically distressing (CITE). Brain scans reveal that social rejection activates the same brain areas linked to physical pain (CITE). In short, being left out doesn’t just hurt emotionally—it can feel like real pain.

Affiliation in Groups

Groups do more than fulfill our need to belong—they also offer valuable resources like information, help, and emotional support. According to Leon Festinger’s social comparison theory (CITE 1950, 1954), people often join groups to better understand their own beliefs and attitudes by comparing themselves to others.

Stanley Schachter (CITE 1959) explored this idea by placing people in unclear or stressful situations and asking whether they’d prefer to wait alone or with others. He discovered that most people chose to be with others—they affiliate during uncertain times to feel safer and more informed.

While any company can be comforting, we tend to prefer being around those who can give us emotional support and reliable information. Interestingly, in some situations, we’re drawn to people who are worse off than we are. For example, imagine getting an 85% on a Math test. Would you rather talk to someone about mathematics who scored a 95% or someone who got a 78%? Many people would choose the latter, as comparing ourselves to others who are doing less well can help protect our self-esteem. This behavior is called downward social comparison.

Identity and Group Membership

Groups don’t just help us make sense of uncertain situations—they also help us answer one of life’s biggest questions: “Who am I?” While we often think of our identity as a personal, internal understanding of our experiences, traits, and preferences, much of who we are is shaped by our relationships and group memberships. We define ourselves not only by individual qualities but also by our roles, friendships, family ties, and social groups. In other words, our identity is shaped by both the “me” and the “we.”

Even basic traits like age or gender can influence how we see ourselves, especially if we identify with those social categories. Social identity theory suggests that we don’t just label others (e.g., man, woman, student, senior), but we also label ourselves in similar ways. When we strongly identify with a group, we often adopt the traits we associate with that group. For example, if we think of college students as intellectual, we may see ourselves that way if we feel connected to the college student identity (CITE Hogg, 2001).

Groups also affect our self-esteem. According to researchers Crocker and Luhtanen (CITE 1990), we often base part of our self-worth on the reputation and status of the groups we belong to. When we experience a personal failure, we might boost our self-esteem by focusing on our group’s success. We may also feel better about ourselves by comparing our group favorably to others, which can sometimes lead to viewing other groups in a negative light (CITE Crocker & Major, 1989).

Psychologist Mark Leary adds another perspective with his sociometer model of self-esteem. He suggests that self-esteem isn’t just about personal value—it acts as a social gauge. A drop in self-esteem may signal that we’re at risk of being excluded or devalued by others. Like a warning light, it tells us to adjust our behavior or image to maintain acceptance. So, self-esteem isn’t just about confidence—it’s deeply connected to our sense of belonging in the groups that matter to us (CITE Leary & Baumeister, 2000).

Evolutionary Benefits of Group Living

Groups may be one of the most powerful tools humans have developed. They allow people to accomplish goals that would be difficult—or even impossible—to achieve alone. In groups, individuals gain access to resources, protection, and support that they might not have on their own.

According to social psychologist Richard Moreland, groups tend to form when “people become dependent on one another for the satisfaction of their needs” (CITE 1987, p. 104). From this perspective, group life isn’t just convenient—it’s essential.

Evolutionary psychology suggests that the benefits of living in groups are so significant that humans have developed a natural tendency to seek out social connections. Over generations, people who were more social and group-oriented were more likely to survive, reproduce, and pass on their genes. In contrast, individuals who preferred isolation may have faced greater risks and were less likely to thrive. As a result, modern humans are the descendants of those who instinctively sought out community and cooperation. We are, in essence, wired to be joiners, not loners.

Motivation and Group Performance

Groups often form with a clear purpose—whether to solve problems, build things, share knowledge, express creativity, protect one another, or simply enjoy shared experiences. But an important question remains: Do groups always perform better than individuals?

That question leads to deeper exploration of group dynamics, motivation, and the factors that influence whether working together truly leads to better outcomes.

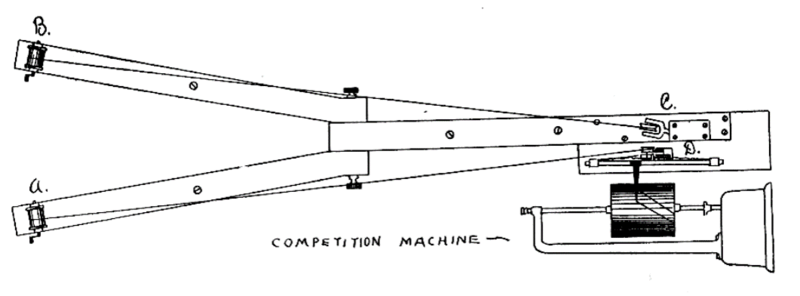

Do individuals perform better alone or within a group? This question was at the heart of one of psychology’s earliest experiments, conducted by Norman Triplett in 1898 (CITE). Observing bicycle races, Triplett noticed that cyclists tended to ride faster when competing against others than when racing solo against the clock. To explore whether the presence of others could psychologically enhance performance, he designed an experiment with 40 children. Each child was asked to turn a small reel (which he called a “competition machine”) as quickly as possible. The results showed a slight improvement in performance when the children worked in pairs rather than alone, suggesting that the presence of others can indeed boost individual performance (CITE Stroebe, 2012; Strube, 2005).

Triplett’s work helped spark interest in what we now refer to as social facilitation—the tendency for individuals to perform better on certain tasks when in the presence of others. However, it was Robert Zajonc (CITE 1965) who later clarified when social facilitation is likely to occur. After analyzing existing studies, Zajonc proposed that the presence of others enhances performance primarily when a task involves dominant responses—behaviors that are well-practiced, habitual, or instinctual. In contrast, if a task demands nondominant responses—those that are new, complex, or unfamiliar—the presence of others can actually hinder performance.

For example, students tend to write less effective essays on challenging philosophical topics when working in groups than when writing alone (CITE Allport, 1924). On the other hand, they tend to make fewer mistakes on simple math problems when others are present (CITE Dashiell, 1930).

In essence, social facilitation is task-dependent: performance improves with an audience when the task is simple or familiar, but declines when the task is difficult or unfamiliar. Several psychological mechanisms help explain this effect. Research on physiological responses, including brain imaging and the challenge-threat framework, shows that we react both physically and neurologically to the presence of others (CITE Blascovich, Mendes, Hunter, & Salomon, 1999). Additionally, being observed can create evaluation apprehension—a concern about being judged—which can increase pressure and influence performance (CITE Bond, Atoum, & VanLeeuwen, 1996).

The presence of others can also disrupt our ability to focus, sometimes helping with simple tasks like the Stroop task but impairing performance on tasks that require deeper cognitive effort (CITE Harkins, 2006; Huguet, Galvaing, Monteil, & Dumas, 1999).

Social Loafing

Groups often outperform individuals. A student working solo on a paper will likely accomplish less in an hour than four students collaborating on a group project. One person alone is unlikely to win a tug-of-war against a team. And a moving crew can pack and transport your belongings much faster than you could manage on your own. The common adage, “Many hands make light work,” captures this idea well (CITE Littlepage, 1991; Steiner, 1972).

However, groups can also under-perform. While research on social facilitation has demonstrated that people can be more motivated when working alongside others—especially on familiar tasks where each person’s input can be tracked—this dynamic shifts when the task demands a true collective effort. For one, group work requires coordination among members to optimize performance, which rarely happens perfectly. For example, in a group tug-of-war, participants tend to pull at slightly different moments, resulting in misaligned efforts. This phenomenon is known as coordination loss. Although the group is stronger than any individual alone, it is not as strong as the sum of its parts (CITE Diehl & Stroebe, 1987).

Another issue is that individuals often don’t try as hard in group settings. When people engage in collective tasks, they typically put forth less effort—both physically and mentally—than they do when working alone. This drop in motivation and output is known as social loafing (CITE Latané, 1981).

To explore both coordination loss and social loafing, Bibb Latané, Kip Williams, and Stephen Harkins (CITE 1979) conducted experiments in which students were asked to clap or cheer, either by themselves or in groups of different sizes. In some conditions, participants actually performed in pairs or six-person groups. In others, they were led to believe they were in groups, but were blindfolded and wore headphones playing masking noise to isolate the psychological effects. While larger groups produced more overall noise, individual output dropped as group size increased. In two-person groups, each individual exerted only 66% of their solo effort, and in six-person groups, this fell to 36%. Even when participants only believed they were part of a group, their performance declined: those who thought one other person was shouting gave 82% effort; those who thought five others were shouting dropped to 74%. Since these “pseudo-groups” removed any coordination challenges, the decline in performance could be explained only by reduced individual effort—clear evidence of social loafing (CITE Latané et al., 1979).